Introduction

China has one of the most promising wine markets in the world (Ambaye, 2015; Mariani et al., 2012). Wine industry in China has a considerable growth in recent decades (Li and Bardaji, 2016). China is one of the top ten wine markets in the world and the fifth largest wine consumer (Li, 2017). However, the production areas of wine are still small and the wine industry has been expanded to meet the consumers’ demand of Chinese’s people (Capitello et al., 2015).

More specifically, since 1980’s, wine industry, as an emerging industry in mainland China, plays an important role for local government helping regional economic development. According to the International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV), the output of wine production in China reaches 1,351,000 ton until 2012, comparing to 700,000 ton of that in 1995. Also, the amount of consumption from 1995 to 2012 increased from 691,100 ton to 1,713,500 ton. This can be seen as a huge potential in the wine market in mainland China to be excavated.

The population of China is large in the world, with the remarkable expansion of middle class in China (Barton et al., 2013). Factors such as the growing middle and upper class, wine-culture and information spreading significantly related to the increase of individual consumption rate (Capitello et al., 2015; Li, 2017). This provides a good wine consumption market basis and is foreseeable that whole wine market would become bigger and bigger in the next decades (Crescimanno and Galati, 2014).

The wine market is a good example of monopolistic competition whereas the market has been evolved by various types, differentiated by cultivated regions and preferences of consumers such as price, favor, brand and taste which led to monopolistic and competitive markets (Rebelo et al., 2017). Like world wine producing countries such as New Zealand, Chile and Australia, China has a key feature of monopolistic competition (Boblik, 2014; He, 2014).

In mainland China, there are only six firms whose annual production exceeds million tons, these firms respectively are Zhangyu, Changcheng, Wangchao, Weilong, Zhongxingguoan, and Tonghua. Among these firms, Tonghua is the biggest and most well-known wine company which located in Tonghua city. In recent years, amur-grape cultivating bases were set up in the Qingshi (青石), Taiwang (太王), Maxian (麻线) cities, as well as counties in Yalu river area. The local farmers made production and sales contract with Tonghua wine company and Tongtian wine company, which are two leading companies in Tonghua area, and also other small-scale wine companies. Except for the two big wine firms and few small wine firms, there are also lots of small wineries which produce wine with home-grown grapes and do not make contract with local grape farmers, some even have their own wine store in the city.

In these circumstances, wineries were built and grew in the latest 20 years, most wineries develop as few big strong monopolistic companies rather than a bunch of small wineries. These big firms such as Changcheng, Zhangyu, own lots of small wineries and production bases in different area. These big firms located in the main production areas possess more than half of the consumer market. Hence, the following questions are the main subjects this paper talking about: how do these small wineries survive among those big giant companies? How can small wineries improve their competitiveness and chase up the pace of industrial upgrading? Is there any way for them to use their particular advantage to challenge those firms in the domestic market and seize their own share of cake? This study tries to find out the key factors to enhance the competitiveness of small wineries, taken Tonghua city as study region.

With those circumstances, the local government puts forward policies that build an economic region of wine in the Yalu river valley. The ‘Yalu River Valley’ strategy first came out in 2013 by the department of characteristic industrial development of Ji’an city (attach to Tonghua city), following the example of Napa Valley and other wine clusters aim to enhance the wine industry competitiveness in Tonghua area to promote local economic growth.

Many researches focused on Chinese wine market such as consumer preference and behavior for wine (Capitello et al., 2015; Higgins et al., 2014; Lockshin and Corsi, 2012; Tang et al., 2015). Some studies concentrated wine production and distribution channels in China, demonstrating regional structure of China’s wine market (He, 2014; Sun, 2007). To identify key determinants to succeed in the wine market, previous study had been carried out in the historical evolution of Chinese wine industry (Jenster and Cheng, 2008). Case studies were provided to show various marketing strategies to the wine producers (Dana et al., 2013; Doloreux, 2012; Pamela, 2004). Economic performance in an increasingly globalized wine business was investigated to guarantee the industry’s competitiveness (Flores, 2018; Montaigne and Coelho, 2012). And there are many works related to change in wine consumption trend and impacts on production differentiation in old and new world wine countries with respect to demand, supply and institutional perspectives (Fleming et al., 2014). However, few consideration, however, has been paid to the insight from a policy makers’ perspective. This study is articulated in an effort to show the lack of practical suggestions on wine industry targeting small wineries’ competitive strategies.

Thus, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the wine industry competitiveness at Yalu River valley in China, and to find out the main indicators affecting the competitiveness of wine industry in Yalu river valley. This contribution explores implications and suggestions to strengthen small wineries and wine firms’ power to form a wine cluster under the Yalu River valley strategy.

Materials and Methods

The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) method is suggested by Saaty (1980). Its additive weighting method for multi-criteria decision problems helps to capture both subjective and objective aspects of a decision maker’s evaluation, thus reducing the bias in the decision-making process.

In this paper, we use AHP method to develop a generic model of competitiveness that explains the complex relationship between competitiveness indicators and drivers. This approach offers a deeper understanding of competitiveness because it helps to identify the degree to which a specific performance indicator is important to the firms within an industry and how it reflects the competitiveness of that particular industry. In addition, it helps evaluate the extent to which each driver affects the indicators. Therefore, the AHP model can be used to solve practical problems that arise when devising strategies to improve competitiveness (Sirikrai and Tang, 2006).

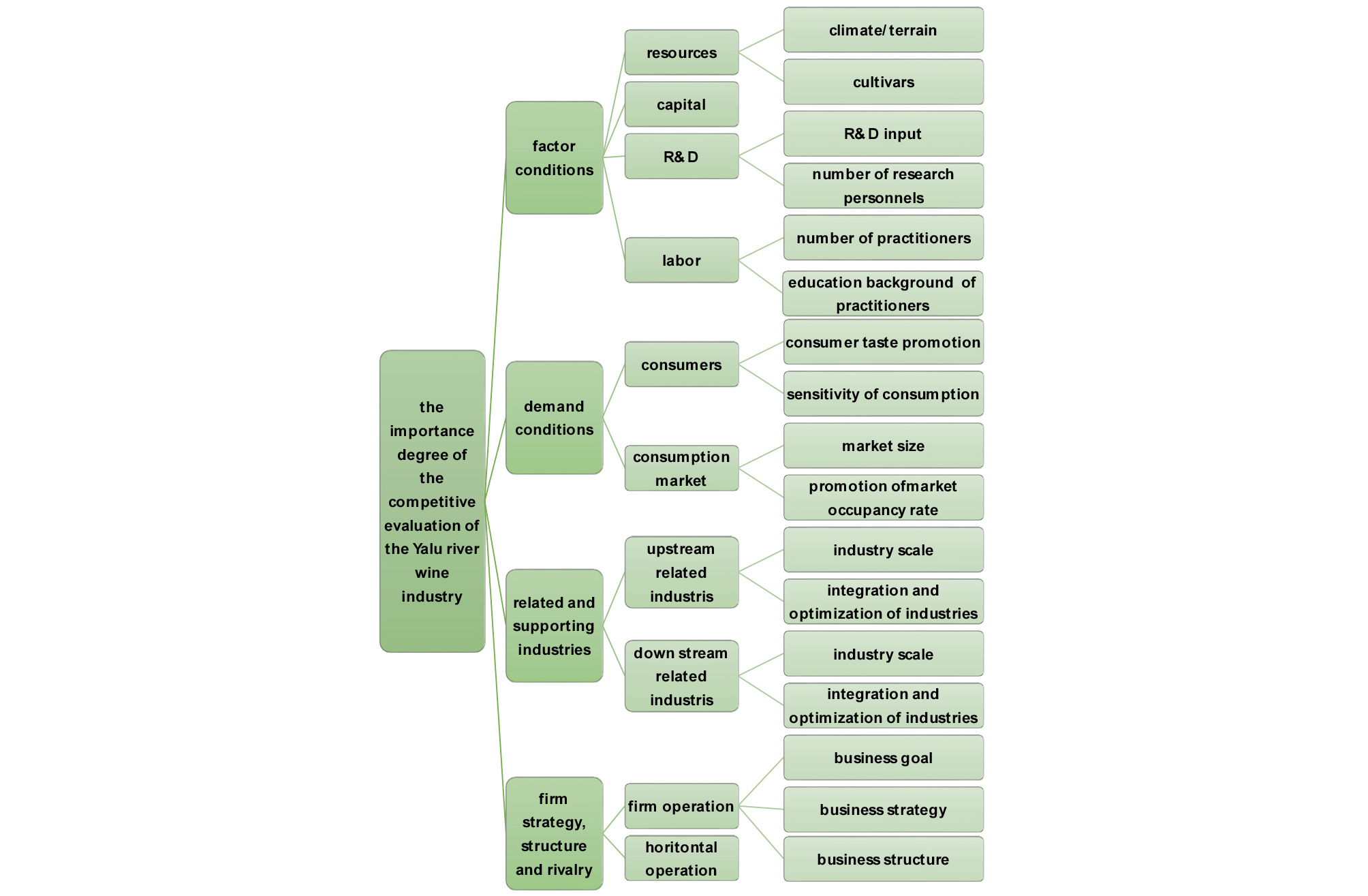

The structure of AHP model was built according to Porter’s diamond model, shown in Fig. 1: an overall goal on the top level, criteria based on diamond model on the first hierarchy which contribute to the overall goal, sub-criteria on the second hierarchy which contribute to the criteria on first hierarchy, and alternatives on the third hierarchy contribute to the sub-criteria on second hierarchy.

Over last decades, the term ‘competitiveness’ has been widely used. One notion of competitiveness is the comprehensive ability for two or more competition subjects that is revealed in the process of contention and competition towards an aim or interest. This definition contains the context on a national level and a regional level (Wang, 2013). Also, Porter insists that the determinants of productivity and the rate of productivity growth are important to understand competitiveness, we must focus not on the economy as a whole but on specific industries and industry segments (Porter, 1990).

In this study, we combined Porter’s standpoint with the notion of competitiveness by Wang (2013), that the competitiveness in a regional industrial level is the comprehensive ability for two or more competition subjects that is revealed in the process of contention and competition towards an aim or interest. The competition subjects are industries in different regions. The aim of competitiveness is to gain market share and economic benefits in a long run. The competition process reflects the influence and function mechanism of the competition results.

Porter came up with the diamond model and analysis framework for competitiveness and strategy by competitiveness trilogy. In his opinion, the factors that can determine competitiveness are not only the natural resources or labor any longer, but also the productivity that takes innovation. The productivity not only means the technology innovation, but also includes policy planning, system design, and personal training or so.

In Porter’s Diamond model, there are four main determinants, and two exogenous factors—chance and government, also play a role in shaping the environment for competing in particular industries. In this study, we only adopt the four main determinants to analyze the evaluation of regional competition in a particular industry.

Porter also appeals that industrial cluster is an agglomeration of spatial adjacent and interrelated firms and organizations. Through mutual linkage and interaction among each sector, it can generate an external economy and promote innovation through business trust and cooperation (Wang, 2013). Clusters encompass an array of linked industries and other entities important to competition. They include, for instance, suppliers of inputs, and infrastructures. Clusters also linked to downstream industries which containing institutions and services that provide training, information, research, and technical support (Beer et al., 2003). To enhance the competitiveness of small wineries in Tonghua, forming a wine cluster is in consistency with the Yalu River valley strategy.

The AHP method considers a set of evaluation criteria or options among which one is more important. The scale of evaluation criterion is from 1 (equal importance) to 9 (absolutely more important), the higher the score, the better the performance of the option with respect to the considered criterion.

The first step of AHP procedure is to compare pairs of alternatives with respect to each criterion and pairs of criteria and calculate the eigen value. The second step is to synthesize judgements and obtaining priority rankings of the alternatives with respect to weight of each criterion and the overall priority ranking for the problem, the AHP combines the criteria weights and scores, thus determining a global score for each option, and a consequent ranking. With a list of the relative weights and importance. Last, the consistency index (CI) and consistency ratio (CR) can be calculated to measure how consistent the judgments have been relative to large samples of the judgments. The CR which is exceeds 0.1 could be considered as inconsistency and untrustworthy. If CR equals 0 then it means that the judgments are perfectly consistent.

The questionnaires were sent out and received from August to October in 2016, valid questionnaires of 48 were taken back. The survey was designed in order to develop wine industry in Yalu river valley in next decades, considering the factors that would affect the competitiveness of wine industry in Yalu river valley, and find out which one of them would be more important.

The basic demographic information of these 48 survey respondents are as shown in Table 1. Among 48 respondents, 77.1% are male, 22.9% are female. Age above 40 and 50 charges 33.3% and 31.3%, in turn. 50% respondents are master or doctor degree, and 37.5% respondents are undergraduate. There are 39.6% respondents are working less than 20 years, 33.3% of people are working less than 10 years and 20.8% of people are working less than 30 years. The wine producers charge 35.5% of total, and 64.6% respondents are wine related experts. The explanation of criteria of the AHP structure we built is shown in Table 2. The criteria on fist hierarchy are selected based on diamond model, and the criteria on second and third hierarchy are selected based on competitiveness evaluating index system of regional industry by Wang and Xie (2013), Yu and Sun (2005), and Sun (2007).

Table 1. Demographic information of survey respondents

Table 2. Content of criteria

The description of criteria comparison results is demonstrated in Table 3. Mean value shows the importance degree. The evaluation of importance comparison was assigned with a scale of 9 degrees from equal important (1) to absolutely more important (9), the positive sign of mean value means that the criterion on the left side (for instance, in Table 3, comparing to demand conditions, the factor conditions is the left side criterion) is more important, and the negative sign means that the criterion on the right side is more important.

Table 3. Description of criteria comparison result

In the first hierarchy, both factor condition and demand condition are somewhat more important than related industries. Factor condition is slightly important than demand condition and firm rivalry. And demand condition is slightly important than firm rivalry. Related industry comparing to firm rivalry shows a negative sign which means that it is less important than firm rivalry in a minor degree. In the second hierarchy, resources factor is much more important than labor but shows unimportant comparing to R&D. Capital and R&D are much more important than labor. The resources factor shows slight importance comparing to capital and capital is slightly important than R&D. Consumers are unimportant comparing to market in a minor extent. Upstream industries are more important than downstream while firm operation is more important than horizontal competition. In the third hierarchy, cultivar is slightly important than climate and terrain. R&D input is more important than personnel. Education is much more important than numbers of labors. In addition, consumer taste is less important than consumption sensitivity. Market size is less important than market share. In terms of related industries, farm size is less important than farm organization, integration of industry is mildly important than industry scale. With respect to factor of firm rivalry, business strategy is much important than firm structure and business goal, and business structure is slightly important than business goal.

There are four main wine producing regions in China: Xinjiang province, Gansu province, Shandong province, and Hebei province. The information of climate, solid, terrain and tradition in Tonghua region is shown in Table 4. In these areas, mainly cultivated are common grape varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Riesling and Chardonnay and so on. However, in the northeast of China, in which Jilin Province is located, have its local grape varieties. In Jilin, because of the cold weather, the grape type of ‘Vitis Amurensis’ has been cultivated. Tonghua is the main city of producing Vitis Amurensit grape (hereinafter referred to as amur-grape) in Jilin Province, this kind of wild grape is a good raw material to make ice wine. Tonghua is the largest amur-grape producing area. In 2013, the amur-grape cultivated area reaches 1,400 ha, output reaches 20 thousand ton and 60 million RMB.

Table 4. Terroir of wine in the Tonghua area

As to consider the natural resources of producing wine, there is a saying ‘7 credits for raw material, 3 credits for production technology’ to evaluate the quality of the wine. Thus, it is important to consider the quality of grape that the wine production would use, and the terroir must have to be taken into account to measure if the quality of grape is good.

Results

Table 5 shows the priority of catalog in the 1st hierarchy. The result in the 1st hierarchy shows that factor condition (0.306) is the most important criterion, followed by demand condition (0.298), firm strategy, structure and rivalry (0.237), and related industries (0.159). However, the experts think demand condition (0.306) is the first criterion, followed by firm strategy and rivalry (0.275), factor condition (0.268), related industries (0.151), in turn.

Table 5. Priority of catalog in the 1st hierarchy

Table 6 displays the priority of sub-criteria in the 2nd hierarchy. The result of catalog ‘factor’ in the 2nd hierarchy shows that R&D (0.420) takes the first priority, and second criterion is capital (0.291), the third important factor is resources (0.215) and the last one is labor (0.074). Different from experts’ view, producers recognize that labor (0.122) is more important than resources (0.191), which may be because the grape gatherer have to be trained to pick up grapes in a short time in case of the water inside grapes getting melted. The result of catalog ‘demand’ in the 2nd hierarchy shows that consumption market (0.445) is more important than consumers (0.555). The development of consumption market provides a good chance for small wineries to survive and grow. However, the producers may want more concise link with consumers since many producers don’t know the consumer’s need very well. Also, they may consider information asymmetry as an important factor. The result of catalog ‘firm strategy, structure and rivalry’ in the 2nd hierarchy shows that firm operation (0.582) is more important than competition (0.418). Since the Yalu river valley wine industry is a newly formed wine agglomeration, firms are get onto the track not too long ago, their aim is to survive and manage well in the primary stage, rather than compete with others. The result of catalog ‘related industry’ in the 2nd hierarchy shows that upstream industry (0.583) is more important than downstream industry (0.417), upstream industry may directly affect the quality of wine production.

Table 6. Priority of sub-criteria in the 2nd hierarchy

Table 7 demonstrates the priority of alternatives in the 3rd hierarchy. The result of sub-criteria ‘R&D’ in the 3rd hierarchy shows that R&D input (0.662) is more crucial than personnel (0.338). The result of sub-criteria ‘resource’ in the 3rd hierarchy shows that cultivars (0.563) is the main factor because the improvement of new variety directly influence the cold-resistant ability of amur-grape. The result of sub-criteria ‘labor’ in the 3rd hierarchy shows that education background (0.789) is in the first priority, this may because well-educated labor results in good cultivating and wine-making techniques. The result of sub-criteria ‘consumption market’ in the 3rd hierarchy shows that, market occupation rate (0.541) is a more important criterion. Firms’ aim is to survive in the fierce competition at the prime stage, so enlarging the market share is more crucial to them. However, experts hold different opinion since they see that market size is crucial because domestic consumption has huge potential to grow. The result of sub-criteria ‘consumers’ in the 3rd hierarchy shows that sensitivity of consumption (0.568) is more important than promotion of consumer taste (0.432). The sensitivity of production price, awareness of brand and origins. These have a relative relationship with the competition. However, the producers pay more attention about how to make better wine since the nitpicking of consumer can spur the increase of production quality. The result of sub-criteria ‘firm operation’ in the 3rd hierarchy shows that the priority goes to strategy (0.557), structure (0.241), and business goal (0.241), in turn. The firm strategy decides business mode directly. Structure related with the management of a company. In experts’ view, goal is more important than structure. Business goal could affect strategy. However firm structure is relative to its operation. The result of sub-criteria ‘upstream industry’ in the 3rd hierarchy shows that the organization of farmers (0.544) is the more crucial factor. Information gap between wine producers and farmers can cause the low productivity and low quality since they lack of a channel for communication. Especially, the grape procurement modes are without a supervisory countermeasure. Experts believe that industry scale may lead large output, of which impact can also results in sales volume and origin awareness. The result of sub-criteria ‘downstream industry’ in the 3rd hierarchy shows that, industry integration (0.578) is more important because a good industrial integration results in transaction cost-reduction, efficiency of resource allocation, attraction of new firms, form of creative and innovative atmosphere, and so on.

Table 7. Priority of alternatives in the 3rd hierarchy

Table 8 gives the total priority ranking of each criteria. In the catalog of ‘factor’, R&D (0.480) is the most important criteria, while capital (0.291) is the second important criteria, and then resource (0.215) and labor (0.074), in turn. The R&D input (0.662) contributes more to R&D rather than personnel (0.338). Cultivars (0.563) contributes more to resource than terrain (0.437). Education (0.789) rather than the number of labors (0.211) contributes more to labor. In the catalog of ‘demand’, market (0.541) is more important to consumer. The occupation rate of market (0.541) rather than market size (0.459) contributes more to the wine market. The sensitivity contributes (0.568) more to consumer than taste (0.432). In the catalog of ‘firm, strategy, structure and rivalry’, firm operation (0.582) is more important to competition (0.418). Strategy (0.557) is more important and followed with structure (0.241) and goal (0.202), in turn. In the catalog of ‘related industry’, the upstream industry (0.583) is more important than downstream industry (0.417). The organization of farmers (0.544) is more important than farm size (0.456) to the upstream industries while integration and optimization (0.578) contributes more to downstream than industry scale (0.423).

Table 8. Criteria priority ranking

Discussion

According to the survey result, factor condition is the most important factor followed by demand condition, firm strategy and rivalry, related industries, in turn. Since the factor condition ranks No. 1 according to the result, we can say that the most important indicator of concern to respondents is the factor condition, which is, also can be seen as the quality of wine. This is probably because when considering whether a wine production has a good quality which usually means the fine aroma, the nature resources of the grape growing area, the solid, climate, frost free period and the most important condition of ice wine, temperature, etc. Also, the R&D is important to find new cultivars, especially to work out a better cultivar to be more cold resistant, or to balance the sweet and sour and tannin. The improvement of R&D can benefit in many ways such as the information exchange, processing technique, especially the new grape variety. R&D can enhance the productivity and the cold-resistant ability of grape, which is a very important factor to the wine quality. The R&D institutes are dispersedly located. The present research institutions are as follows: the R&D center being built now, research institutes owned by two big companies, local specialty research center, related universities (Jilin Agriculture University, Jilin University, Chinese Agriculture University and the Northwest Agriculture University) and wine association. The R&D sources seem to be a lot, however, each of them is separated and are not well linked, barely share information with others. Capital is used for winery construction and equipment input. In addition, labor could affect the quality of wine product, especially for ice wine. The local wine industry at present stage, the main target is to promote the quality of wines.

Demand condition ranks No. 2 which is slightly lower than the factor condition, but much greater than the other factors mainly because of the brand impact of the Tonghua wine. First, according to the results, the need and nitpicking of consumers can stimulate firms within cluster. The benign nitpicking can be encouraged by wine knowledge training, which can lead to reduce price and to promote awareness. In addition, the small wineries and wine firm owners have either benefit or disadvantages, the awareness of Tonghua wine as the wine production origin, can radiate from Tonghua. Especially with circumstance of the consumer market getting bigger and bigger each year, the market and consumption trend is transforming and upgrading, which is a good chance for the small and new firms to find their position and gain a piece of market share. Hence, the leading effect of big companies is crucial, and the small wineries within the cluster should have a good relationship with leading companies. The information and social networks among firms and institutions plays a crucial role to the success of California wine cluster (Mueller et al., 2006).

Firm structure, strategy and rivalry ranks No. 3, according to the status of the two leading firms in this area, Tonghua wine company and Tong-tian wine company. Both companies walked on a road with a strategy emphasizing more on the capital operation. Since the ‘fake wine’ affair happened in the recent years, however, both firms could not focus on the production itself anymore. This kind of strategy and structure change resulted in about 70% of Tonghua wine with low quality (its 30% with high quality). Because of this unhealthy management strategy, bad influence also has given to the horizontal rivalry. Tonghua and Tong-tian companies basically can represent all Tonghua wine, because of their well-known brand. Low quality of wine from two companies cannot bring good reputation to small wineries and firms in Yalu river valley. So there is no way for small wineries to have competitiveness against those big-scale companies, and low competition brings less stimulations and positive role to big companies either. This leads to a never-ended circulation, if the companies don’t make a change. Thus, the business strategy and goals should be in accordance with the circumstances of the prime stage.

Related and supporting industries ranks No. 4. Through field research, farmers reported that local wineries and firms implementing ‘farmers plus firms’, ‘producing base plus firm’, and ‘farmers plus association (agent) plus firm’ mode. The wine firms buy grapes from farmers, or agents or their own producing base. Usually the vineyards belong to and are managed by local farmers. Besides, under the ‘farmers plus firm’ mode, the consistency protocol in terms of grape quality between the farmers and firms didn’t reach a consensus since the wine production requires high quality of grape by considering the shape and color of the grapes. In the raw material purchasing process, firms lose their advantages. But this situation usually won’t happen on the small wineries since they could control grape’s quality. The downstream is mostly out-sourcing to deferent companies of agents. It is hard to reach a hand on them, and they are not geographical concentrated, which may lead to high logistics cost. Furthermore, the collaborations among each sectors and entities is a key factor to boost the wine cluster (Dana and Winstone, 2008). Also, the entry of other industries is important, the entry of wine tourism, food and restaurants helped California wine cluster won good reputation and attracted purchasing power (Mueller et al., 2006).

In summary, based on the results, factor condition is the most important category in the priority list, followed by domestic demand condition, firm strategy, structure and rivalry, and related industry. To subdivide each category, the R&D ranks the top priority among each sub-criteria of the factor condition, then followed with capital, resources and labor. In the sub-criteria of domestic demand, consumer market is prior to consumers. As for firm strategy, structure and rivalry, firm management is placed before rivalry. Last, as for the related industries, upstream industries come first before downstream industries. Based on this, a wine cluster should be built, with the government making positive and effective efforts for inviting investment and business friendly policies, and work together with local wine firms and small wineries to keep the long run in emphasis on R&D especially the input. In addition, the R&D should play the role of linking with each related up- and downstream procedures for integrating and extending the industry chain as well as pulling in the tourism industry since the tourism can brings simulative source to the wine industry. Meanwhile, each firms and wineries in the cluster should reach a consensus on one development strategy or guideline. Besides, the leading firms should play a vital part in information sharing and leading small wineries. Eventually a wine cluster should be built in Yalu river valley with the collaboration, linkage and consensus among R&D institutes, farmers, associations, agents, firms (wineries), government, distributors, retailers and customers.

There are limitations to this study. The primary limitation has the small sample sized and targeted in a single region of China. It would be helpful in a future study to increase the sample size to other wine firms in different regions and it would be interesting to combine marketing strategies considering international wine industry to climate change. The used methodology may be extending to further researches on global competitiveness in international wine industries markets and considering consumer patterns for wine by Chinese societies and world traditional wine-producing countries.